Winter 2018

Blues Farley,

Our Family

Friend

Mono No

Aware, All

Things Must

Pass

Second Edition,

Better Than

the First

Interview

with Robb

Scott, Editor

and Founder

![]()

/Index/

/Letters/

/Profiles/

/Search/

/Podcasts/

![]()

Subscribe

for free!

A New Vocabulary Lesson in Japanese

With a Few Digressions

This is the article that often doesn't get finished. The other evening, I put my heart and mind and my soul into composing two stories written out of love and a spiritual yearning. This story is the third one, which I never got to that night and which everyday ordinary distractions of life nearly have prevented me from even starting.

The idea comes from a phrase in Japanese that I learned five weeks ago when I found it on one of the cards included in a coffee table card set gifted to me by my daughter, who thought I would appreciate finding out about special words and concepts from other languages that do not translate neatly into English.

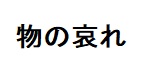

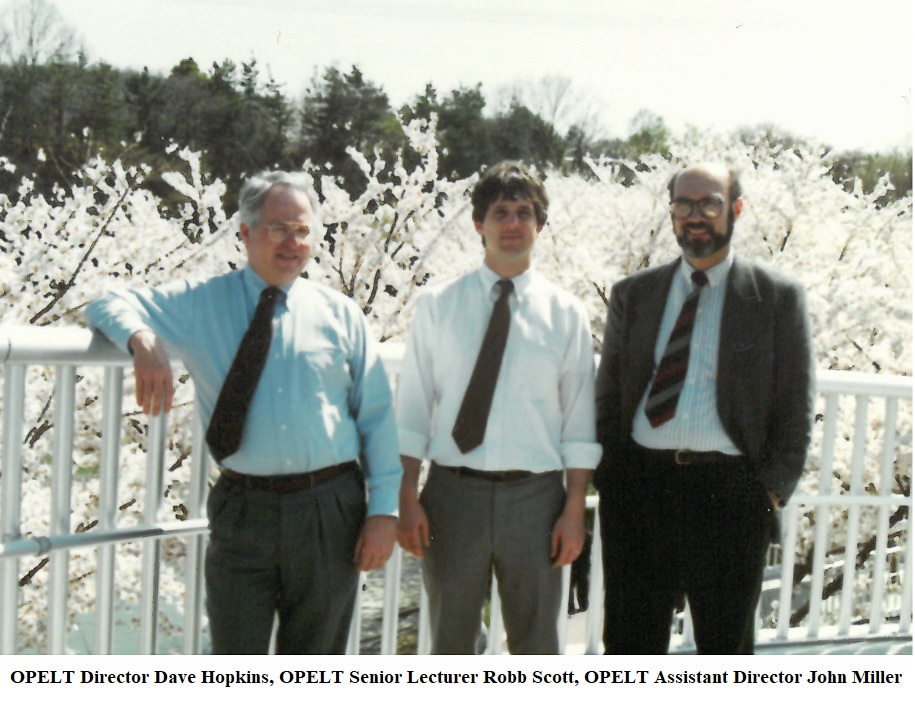

Since discovering this Japanese phrase, I have found myself using it to explain a certain kind of feeling I actually have experienced many times in the six decades I have been living. I am slowly working towards adding the new phrase to a short list of stock words in Japanese that have stuck with me since my nearly five years spent working in Japan in the late eighties and early nineties.

These other words are: 1) Aruku ga ski des - I like to walk, 2) Yoroshku - Nice to meet you and let's work together nicely, enjoyably on whatever we are here to do, 3) Mai tenah koreeyah sue goiy - Wow, in Nagoya dialect, and the always useful words like 4) domo arigato - thank you, 5) oishee - delicious, 6) ee tah daki mas - let's start enjoying this meal, and 7) sue mee mah sen - excuse me for my error or poor etiquette which may have offended you.

You the reader may be wondering how someone could live five years in Japan and survive on only these seven words. I can tell you it helped that I happily ate every new dish that was offered to me and it also helped me bond with male colleagues the fact that I enjoyed drinking cold Japanese beer and hot Japanese sake in social settings. Also, at that time in Japanese society, in all but the most remote towns and villages, people were mildly interested in learning English and also were very, very patient with me and with other gaikokojeens, or, to use the less formal vernacular, gaijins.

But I digress.

I remember one day when I was in high school and my dad was driving me out to our local airport to meet up with Bud Pinkston for my next flying lesson. I was feeling a little under the weather and as children we were used to asking my dad for antihistamine, which he carried in a small metal container always in his pocket. But that morning he explained to me that when you are in the moment of an engaging activity like piloting a plane, you tend to forget about your sore throat or your sniffles, so he did not give me any medicine and he was right and everything went well.

Those two examples of lessons I learned from my father were moments to relish and savor, but I did not have a full enough understanding of life to appreciate the transitory beauty of such experiences, so I was not aware of a sensation like the one I am striving to introduce in this article I am writing now.

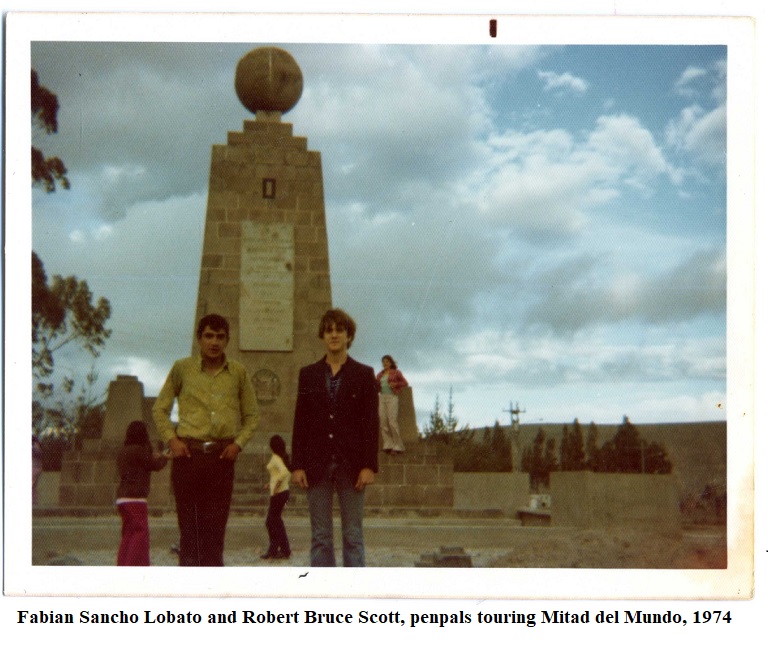

Less than a year and a half after that trip to Chicago, I found myself in another setting poignant with meaning, sitting with my two brothers and my sister and our church pastor, Bruce Backensto, on the grass next to Sterling Lake, where my parents had their first date when they were both students at Sterling College, nearly 30 years earlier. It was a Sunday afternoon and we were planning the funeral service for my mother and father, who had perished in the crash of our plane on landing the day before at what today is called Dwight D. Eisenhower International Airport in Wichita. I suggested that the service ought to be in the morning because it is a more hopeful time of the day, and none of the others disagreed, so that is what we did. I also said that I thought the caskets ought to be closed, and I was informed by my older brother and sister and Rev. Backensto that no other option was available, given the conditions of our parents' bodies.

In the intervening years since that Sunday afternoon conversation in October of 1975, I have often visited Sterling Lake. All of my children know the importance of Sterling, Sterling cemetery, Sterling College, and Sterling Lake in our family. The last several times I was there it was a little windy, and there is a nice bench where I like to sit under the shade of tall trees, and feel the breeze and see the ripples it makes along the top of the water. In Tokyo, the year I worked there, I used to take my lunch over to a little park called "Shiba Rikyu," next to the Hamamatsucho Station on the Yamanote subway train line. I always felt it was amazing how the city noises outside of the park were not noticeable from within the park, and I liked to lay myself down on one of the benches there and close my eyes for perhaps five or ten minutes of true peace, before leaving the park and walking back to work two blocks away.

Even for those like me from the late end of the Baby Boomer generation, our lives can sometimes seem to be the foreground in harmony with a background music score largely dominated by the Beatles. There is a song called "In My Life," which comes to mind and reminds me of "people and places" that, from one perspective, were already ending even as we were only just realizing what a nice time we were enjoying together.

In the Museum of Modern Art, also in New York City, there is a large Jackson Pollack painting, "One: Number 31, 1950." When I lived in New York in the nineties, there was a nice viewing bench about two yards in front of where this very large painting, with it's black and white and brown and dark green splotches, was displayed. I used to like to sit and look at this painting for 10 or 15 minutes at a time, if no one else needed the bench.

As I understand, the Japanese term "Mono no aware,"

The card with this Japanese phrase on it also said that most people who utter these words are at the same time reminded of the short-lived glory of cherry trees in full blossom before the blossoms fall away.

2018 ESL MiniConference Online

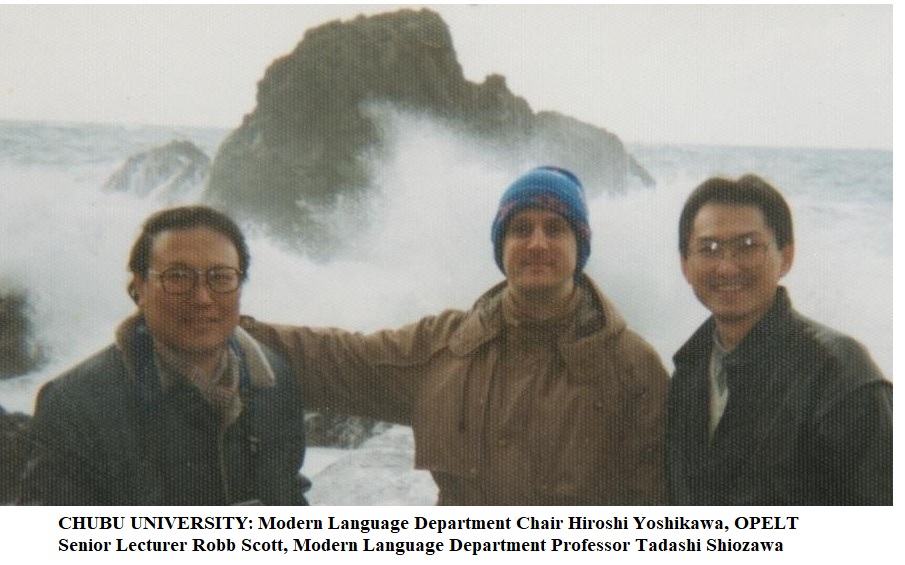

In the first little village where I worked and lived, traditional customs such as bowing when you greeted someone were still observed, and I picked up this habit so completely that in another country, where I found myself needing to get documents for processing my daughter's birth certificate, I genuflected so automatically that when I was leaving that office, one worker said to the other one, in Spanish, "I wish everyone were so polite."

Another time, when I had a restricted driver's license, and was not driving by myself very much yet, my dad, my younger brother, Bill, and I were on a drive up to Chicago to bring back a nice sailboat, a Columbia 26 that my father had decided he needed. We took advantage of the opportunity for me to get some experience with interstate highway driving, and I was at the wheel as we began getting closer to Chicago and were entering more complex trafficways.

I glanced over at my dad a few times, but kept my focus on the road ahead and on all the cars behind us, next to us, and in front of us, and I was starting to get a little nervous, but also I felt lucky to be doing what I was doing, even though misgivings and self-doubt were beginning to creep into my mind. The following five minutes seemed like an eternity, and then my dad told me to pull off at the next exit, a maneuver which I managed to perform without putting our lives at risk, but just barely. When I came to a stop, with a great sense of relief, I heard my father's voice saying the words that I have never been able to forget: "Those five minutes of driving are worth five years of driving in Kansas."

There is a painting by Monet in the Frick Collection, in New York City, called "Vétheuil in Winter." The first time I saw that painting, I gazed in wonder as sprays of water seemed to be emanating from near where several figures are rowing a boat. I felt transported by that experience for that moment in time.

That year that I lived in Tokyo, my apartment was in Musashi-Kosugi, about a 25 minute walk from the station. During cherry blossom season, I loved walking along a little canal that was lined with cherry trees, and it was really something to breathe that perfumed air as I walked near to the trees and experienced the beautiful sensation of seeing and feeling the cherry blossom petals that were drifting down around me like giant snowflakes, eventually landing on the sidewalk or on the water flowing through the canal, or drainway.

refers to an acute awareness of, or enhanced sensitivity to, simultaneously, intense beauty and inevitable loss, the fleetingness of an experience, so that a deep sadness accompanies any enjoyment because one is conscious of the transitory nature of all things.

By Robb Scott

DrRobbScott@gmail.com