September 2003

Achievement Profile: David Nunan

Jo Gusman on Raising Literacy Skills in Elementary ESL

Multiple Perspectives on Plagiarism?

Grandma's Tortillas: Book Review

![]()

/ Index /

/ Letters /

/ Search /

![]()

Subscribe

for free!

Trust and Inclusion in Elementary ESL

Report on Jo Gusman Workshop in Garden City

Many of the participants at the CLD Institute, held

at Garden City Community College, were

teachers from Garden City schools, taking advantage

of the proximity and relevance of this learning

opportunity organized for them by Dr. Linda Trujillo,

Title III Coordinator for Garden City's USD 457. A

good number of attendees also traveled from as far

away as Lawrence, Kansas, to the east, and Torrington,

Wyoming, to the west.

A White Water Rapids of Consciousness

"Stream of consciousness" is a speaking style which

can sometimes be quite effective in creating a

learning environment with sustained high levels

of interest. This mode of discourse is often

contrasted with more deliberative styles, in

which presenters make certain the audience gets

enough of a chance to perceive the logical form

of the information being shared. Neither of these

typical patterns of instructional discourse fully

captures the unique and engaging style of Jo Gusman,

whose non-stop chatter might best be described as

a white-water rapids of consciousness, interspersed

with plenty of large, smooth rocks where winded

travelers can catch their breath and see the big

picture for a few moments before jumping back onto

Gusman's colorful raft and careening along through

the spray with her again.

The Daughter of Mexican Immigrants

Jo Gusman has unique insights into the experiences

of ESL students because she was an English language

learner herself in a rural school near Sacramento as the child

of immigrant farm workers from a small village near

Guadalajara, Mexico. Her father had a job managing

a big livestock ranch, she told workshop participants,

"and I only heard English when my mom went to clean

the landowner's home." Her experience growing up

in a Hispanic family while attending U.S. schools

gives Jo Gusman extra sensitivity to the challenges

culturally and linguistically diverse children face

still today. The truth is, she says, not much has

changed as far as bias and discrimination against people

of different cultures and languages in America today. Workshop participants--teachers

in Kansas elementary schools--shared Gusman's belief that too many

of their colleagues harbor feelings of prejudice

against the CLD children whose numbers in our schools are

on the increase.

Gusman notes that in Garden City many

businesses now display signs in Spanish,

showing their interest in catering to customers from

the city's vast Spanish-speaking community. But, she

says, in American society "we're still creating our

schools as if all our clients were speaking English."

U.S. businesses understand they need to communicate

with prospective customers from different cultures

and languages, according to Gusman, while "schools

are going the other way." As one example, she pointed

to "English-only" initiatives which limit schools

in their efforts to reach out to all students and

all families.

Expanding Traditional Definitions of Bilingual Education

Most of Jo Gusman's practical ideas for improving

the classroom learning environment for all children

(not just English language learners) have grown from

her experiences in the early 1980s at Sacramento's

first "newcomer school." Gusman, who received her

California teaching license in bilingual education

and biliteracy education, specifically for Spanish-speaking

children, in 1974, encountered a totally new teaching

challenge when she was hired as a kindergarten teacher

at this school in a once-abandoned school building

in Sacramento. Students at the newcomer school had

to meet three requirements: refugee status, immigrant

status and no prior U.S. schooling. By 11:23 A.M. on

her first day at work, she had 43 students who spoke

12-15 different languages, none of which was Spanish.

"I went from being an effective teacher," she recounts,

"in a matter of hours, to being a totally ineffective

teacher."

Part of her recovery came from speaking with other teachers

in the school. "Everyone was going through the same thing,"

Gusman says. The rest of the answer came from her growing

understanding of research about the human brain applied to

bilingualism and biliteracy.

Lessons From Brain Research

According to research summarized by Jo Gusman, in any new

situation the human brain has three questions it wants

answered immediately:

1. Where am I? (What are the procedures here?)

The Affective Filter and Comprehensible Input

Jo Gusman spent a great deal of time clarifying

the meaning of two terms most ESL teachers are

familiar with, from research by Steve Krashen

and others: affective filter and comprehensible

input. She mentioned a number of factors which

strengthen the affective filter, which she describes

as an emotional shield a child will use to protect

himself or herself from further pain or embarrassment.

Jo Gusman described a cycle in which a new student

is teased, often feels sick, is frequently absent,

misses lessons and experiences a delay in language

learning.

If your students show you "attitude," that shows the

strength of their affective filters against your

instructional messages; some students "try to become

invisible" instead, explains Gusman. One vivid moment in the

workshop was when she had several participants stand

one behind the other to show the layered nature of

affective filters, for example, the way in which

a student's disposition is tied to his or her mother

or father's experiences, which in turn are tied to

those of other relatives. Building the relationship

of trust which weakens the affective filter and opens

the channel of communication with a student can be

a long process, requiring patience on the part of

the teacher.

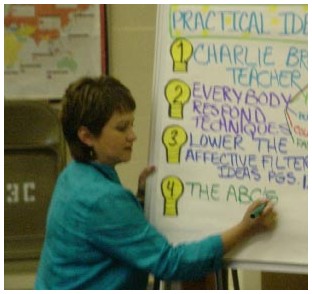

Remember, You Sound Like Charlie Brown's Teacher

There must be a balance struck between the affective

filter and comprehensible input, according to Gusman.

Input is words, concepts, visuals, body language...

everything. Making input comprehensible means, for

example, hooking concepts to prior knowledge, she

explains. In order to help workshop participants

better grok what a teacher sounds like to a new

student in class who comes from a different language

background, Jo Gusman absolutely flabbergasted all

of us by "wonking" like the teacher from the Charlie

Brown T.V. specials for 12 minutes, non-stop. As she

wonked, modulating pitch and tone to simulate normal

teacher-talk, Gusman circulated around the room,

pushing and cajoling individuals to follow her

instructions, using gestures and facial expressions

to show everything from encouragement to exasperation.

About five minutes into this amazing experience, you

found yourself latching onto any hint of meaning to

try to comprehend. During the Charlie Brown wonking,

I also felt a strong urge, which perhaps second language

learners would identify with, to "tune out" and reestablish

inner harmony.

Laying Down a Classroom Communication System

The first set of "practical ideas" which Jo Gusman

shared with workshop participants concerned "Everybody

Respond Techniques," so that children can let the teacher

know how it's going during a lesson. She suggests that

each student can have "a communication bag," which is a

big ziplock bag to keep new communication systems they

make each week in class. In creating new ideas for

these communication system tools, Gusman suggests

thinking about universal systems as much as possible.

Another communication system introduced by Gusman

included "the punctuation fan," which a student can

use to ask the teacher to stop (period), suggest

a pause for reflection (comma), indicate enthusiasm

(exclamation point), ask a question (question mark)

or indicate they have something to say (quotation marks)

by holding the appropriate card from their punctuation

fan over their hearts.

Another item for the "communication bag" is the color-coded

fan. The cards for this fan are cut from bright, flourescent

index cards, with the colors carefully chosen by the teacher

to match a set of four or five flourescent markers or chalk

colors. In math class, for example, the teacher can write

a problem and then four different possible solutions, each

in a different color. As students discover the answer, they

hold up the correctly colored card from their fan. Another

option given by Jo Gusman is a fan with 10 different cards,

each one a different color, numbered 1 through 10. These

can be used for a variety of different multiple-choice

questions or problems.

All of these "communication systems" serve the purpose

of ensuring that everybody in the class gets many opportunities

to respond individually to comprehensible input from the teacher.

These underlying communication systems help the teacher

to create an infrastructure for learning, according to

Gusman.

Establishing Trust in Your Classroom

One nice example of handling a classroom situation in

a way that inspires trust is for the teacher to look at

worksheet activities from a different perspective. Too

often, says Gusman, children striving to learn English

will feel a natural inclination to look at what their

classmates are doing in order to figure out what the

worksheet is about. Instead of interpreting this as

"cheating," teachers should realize the English

language learner is really just "doing research"

to discover what the procedures are.

Once there is trust, inclusion can also be achieved,

she says. If we want to understand how to be inclusive,

all we need to do is look at "the masters of inclusion,"

says Jo Gusman. "Gangs look for the disenfranchised."

She also noted how others, like what she referred to

as "the animal groups" (Elks, Lions, Kiwanis) exclude

certain people, who don't get invited to "network."

"Welcome to Our School" Projects

"There is an illusion of choices," explains Gusman, unless

you are able to network. Teachers need to show students how to

be inclusive." One way she suggests is to have children share their

own stories about their names and their families. Another

is to engage your students in the production of "Welcome

to Our School" videos or Power Points, which can be used

to help orient new families to the community, according

to Gusman, who encouraged workshop participants to

remember the brain's three questions as we guide our

students in designing such projects.

It is a lot easier to prepare for welcoming

new families and their children in our communities

and in our schools if we know they are coming,

explains Jo Gusman, who suggests researching

migration trends at refugeecamps.org,

or consulting local church groups to determine

where they are supporting missionary work (which

establishes a refugee connection and often results

in churches bringing refugees to town).

Don't Overdo It on Phonics

Of these five, according to Gusman, the most

important are "vocabulary" and "comprehension." The most ineffective

of the five elements, taken in isolation, she

says, is "phonics." The key to working with

phonics, says Jo Gusman, is "do it quick, dirty

and move on." Another key she suggests is that

"you eat it, dance it, move it and sing it."

The main problem with phonics, says Gusman,

is that a lot of the sounds don't exist in

an English language learner's first language.

The worst thing a teacher can do is to try to

teach phonics outside of a meaningful context,

she says.

To help teachers remember the five elements

of "phonemic awareness," Jo Gusman introduces

"Ms. Bimss," whose name is an acronym for

"blending," "isolation," "matching," "segmentation"

and "substitution."

Gusman has a lot to say about the fifth

NRC official reading element, "fluency."

She wants teachers to recognize the connection

between the vestibulary system (inner ear

balance) and pre-reading skills. "Move

as you read," she says, suggesting that

the teacher occasionally lead the class

on a marching line around the room as they

are reading out loud. "It is important to

add movement to the fluency process," she

explains, referring to research by Carla Hannaford (Smart Moves: Why Learning Is Not All in Your Head)

and Paul and Gail Dennison (Brain Gym: Simple Activities for Whole Brain Learning).

One of the most important things to teach

children about narrative reading, according to Jo Gusman,

is "instead of focusing on words you don't

know, focus on words you know....Scan for

familiar vocabulary. Then make a movie in

your head. Then make predictions."

Gusman is currently preparing a seminar

for the Bureau of Education and Research

to help teachers deal with the NRC's top

five reading elements. The seminar will

be given in a number of U.S. cities, including

Honolulu. Many other resources to help teachers

and schools more effectively instruct children

from diverse cultural and language backgrounds

are available through New Horizons in Education, Inc.,

of which Jo Gusman is the president. The Web site

is not live yet, but will be www.newhorizonsineducation.com.

The regular mailing address is:

The Third Annual CLD Institute in Garden City, Kansas,

on July 28th and 29th, 2003, brought 150 educators together

to learn from and share with workshop presenters whose

names read like a "Who's Who" of current research and

practice in the instruction of students from different

language and culture backgrounds. The hardest decision

for institute participants was choosing among the great

selection of one-day and two-day workshops, on topics

ranging from early childhood literacy to cross-cultural

dynamics of education for CLD students.

The Third Annual CLD Institute in Garden City, Kansas,

on July 28th and 29th, 2003, brought 150 educators together

to learn from and share with workshop presenters whose

names read like a "Who's Who" of current research and

practice in the instruction of students from different

language and culture backgrounds. The hardest decision

for institute participants was choosing among the great

selection of one-day and two-day workshops, on topics

ranging from early childhood literacy to cross-cultural

dynamics of education for CLD students.

I spent both days in a room with about 40 elementary

school teachers from the Garden City area, learning

about "Elementary Education Sheltered Instruction,"

facilitated by Jo Gusman, of the Sacramento, California,

school system.

I spent both days in a room with about 40 elementary

school teachers from the Garden City area, learning

about "Elementary Education Sheltered Instruction,"

facilitated by Jo Gusman, of the Sacramento, California,

school system.

Jo Gusman has been teaching in California schools

since 1974, and reassured workshop participants that

the current standards craze and seemingly endless

rounds of high-stakes testing which teachers are

stressing under will eventually

pass. "Teachers are responsible today for so many

different sets of standards that the key is to bundle

the standards," she says. "Teachers need time to be

creative again." Gusman shared two of her favorite

quotes to help us understand the personal philosophy

which informs her teaching approach. The first is

a simple idea from Henry David Thoreau: "Less is more."

The second is from Marcel Proust: "The real voyage of

discovery consists not in seeing new landscapes but

in having new eyes."

Jo Gusman has been teaching in California schools

since 1974, and reassured workshop participants that

the current standards craze and seemingly endless

rounds of high-stakes testing which teachers are

stressing under will eventually

pass. "Teachers are responsible today for so many

different sets of standards that the key is to bundle

the standards," she says. "Teachers need time to be

creative again." Gusman shared two of her favorite

quotes to help us understand the personal philosophy

which informs her teaching approach. The first is

a simple idea from Henry David Thoreau: "Less is more."

The second is from Marcel Proust: "The real voyage of

discovery consists not in seeing new landscapes but

in having new eyes."

Her perspective as someone who weathered intolerance

as a student makes Jo Gusman an effective proponent

of inclusion. The worst offense a child in one of her

classes can commit is to not be inclusive, she explains.

Her perspective as someone who weathered intolerance

as a student makes Jo Gusman an effective proponent

of inclusion. The worst offense a child in one of her

classes can commit is to not be inclusive, she explains.

"I was shocked to find I didn't know what to do," explains

Gusman. "I found myself staying later and later after school.

I had to rewrite all my lesson plans." Five months into the

school year, she felt she was still at the same phase and

remembers sitting at her desk crying. "I became paralyzed,"

says Jo Gusman, "and I didn't want to tell anybody." She

had hit "rock bottom."

"I was shocked to find I didn't know what to do," explains

Gusman. "I found myself staying later and later after school.

I had to rewrite all my lesson plans." Five months into the

school year, she felt she was still at the same phase and

remembers sitting at her desk crying. "I became paralyzed,"

says Jo Gusman, "and I didn't want to tell anybody." She

had hit "rock bottom."

2. Who are all of these people?

3. What are we doing today?

"Never forget," says Jo Gusman, "you sound like Charlie

Brown's teacher." That is why it is so important, she

explains, to "set up a communication system in a language

that isn't dependent on English." One of the many analogies

she used was an airport ground crew using Day-Glo wands to

guide aircraft at night, just as teachers need to use

visually distinctive objects to help orient their students

in the classroom.

"Never forget," says Jo Gusman, "you sound like Charlie

Brown's teacher." That is why it is so important, she

explains, to "set up a communication system in a language

that isn't dependent on English." One of the many analogies

she used was an airport ground crew using Day-Glo wands to

guide aircraft at night, just as teachers need to use

visually distinctive objects to help orient their students

in the classroom.

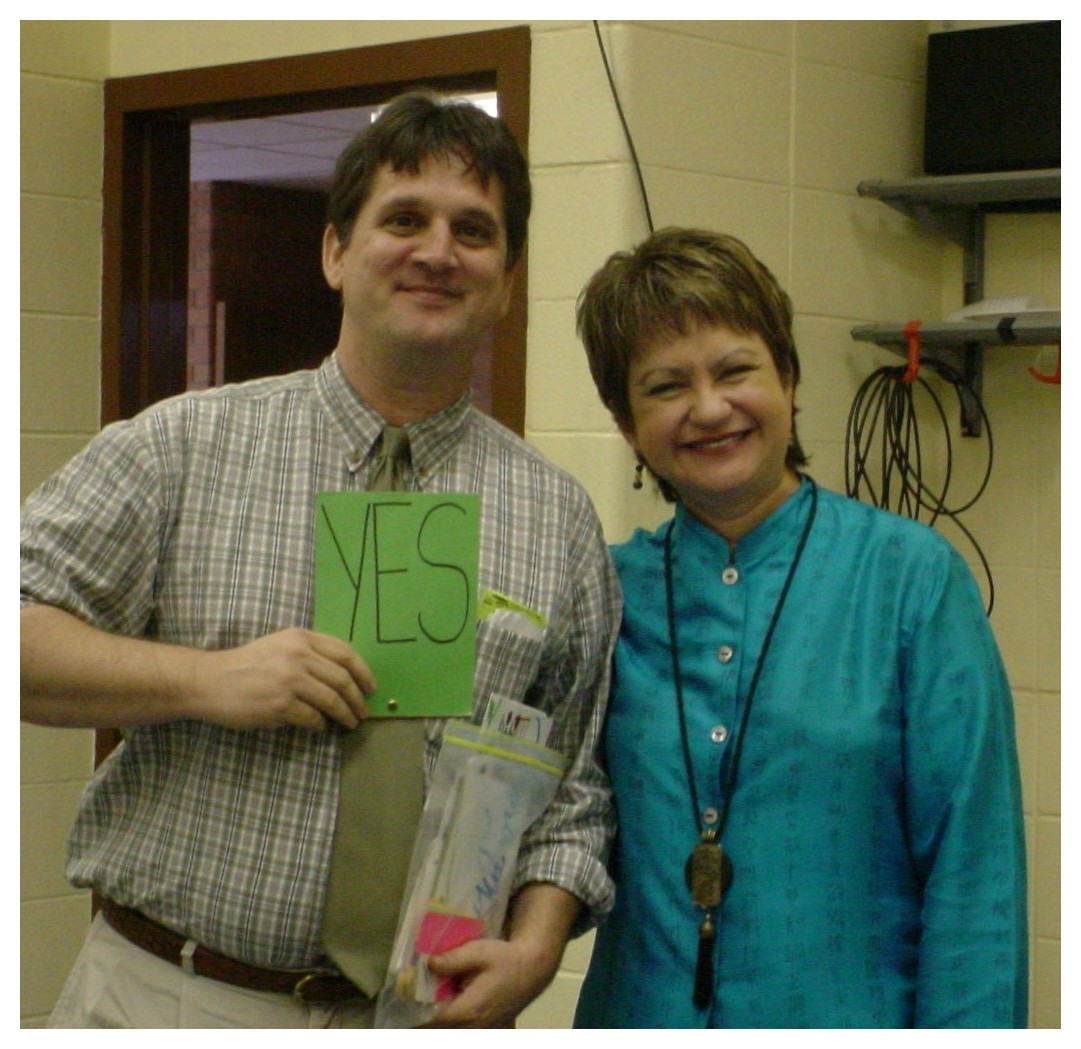

In the workshop, we made "Yes/No Fans," with green

and red construction paper and paper fasteners. On

the green sheet, we wrote "Yes" on one side and "Si"

on the reverse; on the red sheet, "No" and "No." In

a large classroom with many students, this simple

communication system allows everyone to respond at

once to Yes/No questions from the teacher. Jo Gusman

doesn't want her students to wave their answers wildly

in the air; instead, she has them hold the answer over

their hearts so that she can see it. This procedural

matter led her to explain further brain research which,

she says, suggests that the human skin is actually the

outer layer of our brain, and that the human mind

actually resides everywhere in the body. Sources for

this data are Candace Pert (The Molecules of Emotion)

and Robert Sylwester (A Celebration of Neurons: An Educator's

Guide to the Human Brain).

In the workshop, we made "Yes/No Fans," with green

and red construction paper and paper fasteners. On

the green sheet, we wrote "Yes" on one side and "Si"

on the reverse; on the red sheet, "No" and "No." In

a large classroom with many students, this simple

communication system allows everyone to respond at

once to Yes/No questions from the teacher. Jo Gusman

doesn't want her students to wave their answers wildly

in the air; instead, she has them hold the answer over

their hearts so that she can see it. This procedural

matter led her to explain further brain research which,

she says, suggests that the human skin is actually the

outer layer of our brain, and that the human mind

actually resides everywhere in the body. Sources for

this data are Candace Pert (The Molecules of Emotion)

and Robert Sylwester (A Celebration of Neurons: An Educator's

Guide to the Human Brain).

Gusman very

strongly believes that physical movement and coordination

exercises are intimately connected to cognitive activity. She

herself was continually moving around the room throughout

the entire 12-hour, two-day workshop, gesturing with her

hands and her face to accentuate each point, and constantly

throwing out reflection questions ("How many of you...?")

to the audience. These were never single questions, but

rather in series, so that, for example, if she asked how

many of us were classroom teachers and a certain number

of hands were raised, she would modify the question so

that administrators, paraeducators and teacher educators,

in turn, would be included. Every time Jo Gusman asks

a "How many of you.." question, she redirects it again

and again until every member of the group has been included.

Gusman very

strongly believes that physical movement and coordination

exercises are intimately connected to cognitive activity. She

herself was continually moving around the room throughout

the entire 12-hour, two-day workshop, gesturing with her

hands and her face to accentuate each point, and constantly

throwing out reflection questions ("How many of you...?")

to the audience. These were never single questions, but

rather in series, so that, for example, if she asked how

many of us were classroom teachers and a certain number

of hands were raised, she would modify the question so

that administrators, paraeducators and teacher educators,

in turn, would be included. Every time Jo Gusman asks

a "How many of you.." question, she redirects it again

and again until every member of the group has been included.

After going over activities to give everybody many

chances to respond to meaningful input, Jo Gusman returned

to the other key element in a successful English language

learning experience for newcomers in our classrooms: reducing

the affective filter by establishing an atmosphere of trust.

Trust is the first step in creating a productive and inclusive

learning community, according to Gusman. "Take all the time

that it takes to create trust," she adds.

After going over activities to give everybody many

chances to respond to meaningful input, Jo Gusman returned

to the other key element in a successful English language

learning experience for newcomers in our classrooms: reducing

the affective filter by establishing an atmosphere of trust.

Trust is the first step in creating a productive and inclusive

learning community, according to Gusman. "Take all the time

that it takes to create trust," she adds.

Jo Gusman concluded her two-day workshop with

an overview of the National Reading Panel's

key elements of reading instruction, and

how to address these while not sacrificing

all your efforts at reducing affective filters,

increasing comprehensible input and, in general,

maintaining a meaning-rich classroom environment.

Since federal funding for "Reading First"

programs is heavily slanted in favor of the

NRC's dictates, it is important for teachers

to be certain their reading instruction addresses

the five NRC elements of reading: vocabulary,

comprehension, phonics, phonemic awareness

and fluency.

Jo Gusman concluded her two-day workshop with

an overview of the National Reading Panel's

key elements of reading instruction, and

how to address these while not sacrificing

all your efforts at reducing affective filters,

increasing comprehensible input and, in general,

maintaining a meaning-rich classroom environment.

Since federal funding for "Reading First"

programs is heavily slanted in favor of the

NRC's dictates, it is important for teachers

to be certain their reading instruction addresses

the five NRC elements of reading: vocabulary,

comprehension, phonics, phonemic awareness

and fluency.

Jo Gusman

3101 Miramar Road

Sacramento, California 95821-6134

(916) 482-4405

You Had to Be There...

This article about Jo Gusman's recent workshop at the Garden City CLD Summer Institute has failed to convey the enthusiasm for teaching and the sensitivity for different cultural and linguistic perspectives she demonstrated. The above list of practical ideas only touches the surface of the many relevant suggestions Gusman gave during two full days of non-stop instruction. "Some of these ideas will be 'keepers,'" she explained at the start, meaning new activities teachers can use right away. "Others will be 'polishers,'" she added, meaning ways to enhance what we are already doing, because, as her principal at the newcomer school in Sacramento told her back in 1981, "even silver and gold need polishing."

Jo Gusman motivated and challenged 40 teachers in Garden City to go back to school this fall with a renewed determination to help their students succeed. And she gave everyone dozens of ideas and activities to make it happen. "Turn to the person next to you," she said near the end of the two-day seminar, "and tell them 'I am so privileged to sit next to you because you get it.'"

The genius of Jo Gusman's approach to teacher education is that we did indeed feel, for at least that one fleeting moment, like we did really get it. And that experience of that feeling sticks with you, pushing you to recreate it in your own teaching.

I was walking on air as I headed out of this year's CLD Summer Institute in Garden City. I have a greater sense of confidence that I can make a positive difference at school this year.

I understand better than ever before why our teachers, especially our elementary school teachers, deserve our unending gratitude and respect. And I believe, based on Jo Gusman's message, that more and more children from diverse and at-risk backgrounds will have positive school experiences which evoke the same gratitude and respect.

Story by Robb Scott, Hays, KANSAS

Robb@ESLminiconf.net

2003 ESL MiniConference Online