Early

Fall 2013

Mindful

Teaching

by Robb

Scott

Cowboys,

Cossacks

by Robb

Scott

Title tk

![]()

/Index/

/Letters/

/Profiles/

/Search/

/Podcasts/

![]()

Subscribe

for free!

Ideas Are Better Than Stuff:

A Response to Clair Huffaker's Novel

This summer I have been starting my days with early morning walks through a nearby college campus, enjoying the enhanced shades of green in the grass and trees that have been rained on more than usual, especially during July and August so far. On these walks, I generally listen to text-to-speech on my kindle and in recent days this was a book titled "The Cowboy and the Cossack," by Clair Huffaker (1973).

In this story, a team of Montana cowboys join forces with a small contingent of traditional Russian cossacks to safely deliver a herd of 500 cattle to a village in deep Siberia. This morning as the story came to an end, I found myself remembering people I have known in different places around the world, on my limited "tour" of three countries--Ecuador, Japan, and Saudi Arabia--and how much I have learned from those relationships, some fleeting and others still going today.

In this story, a team of Montana cowboys join forces with a small contingent of traditional Russian cossacks to safely deliver a herd of 500 cattle to a village in deep Siberia. This morning as the story came to an end, I found myself remembering people I have known in different places around the world, on my limited "tour" of three countries--Ecuador, Japan, and Saudi Arabia--and how much I have learned from those relationships, some fleeting and others still going today.

In a little fishing village, Nakajo-machi, in the Niigata province of Japan, I got to know Toraichi Kon, a retired postal employee who on several occasions invited me to his home to eat sushi, drink beer, and eat escargot from the restaurant his wife and her brothers operated just a few feet away from their backdoor. I remember one early evening at the restaurant in the company of local fishermen, when I accepted the opportunity to drink hot sake from the shell of a crab after eating the crabmeat. Toraichi Kon and I used to swig beer, pouring to fill each other's glasses, and laugh during our friendly "competition" to determine who was "ichiban."

In Quito, I came to know a local photographer, Ron Jones, who for a few years had corner on the market for giant photo poster prints that advertisers placed between sheets of glass in newly remodeled bus stops. This farmboy from Nebraska built his own plastic cylinder where he would roll big sheets of photographic paper in developing fluids to produce those prints. The two of us had gone to high schools in the states and struck an agreement that his photoshop would provide free film and processing for the journalism students at Academia Cotopaxi, where I was a teacher: in return, Ron came over to the school personally to take individual portraits of every student, which we included in the yearbook and also which he made available as school picture packets at a fair price to their parents, some of the most important business owners and leaders in Quito high society.

It was a lot of work, but also fun, to work with Ron Jones and his co-workers in the red glow of their darkroom, as we developed all the black and white photographs selected by the students and measured to fit into layouts designed by the editors, who were high school seniors at Cotopaxi. The school story section of the yearbook that year was written by one of those seniors, except for one paragraph that I penned, to describe the attempted coup de etat and hours-long kidnapping of President Leon Febres Cordero, rhetorically making it fit into a longer storyline as if it were just a slight variation in the regular stream of school experiences.

I did not get as close to the local inhabitants during my time in Riyadh, a year or so ago, but I do remember a conversation with the Syrian who ran a candy and flower shop at a hospital where I went to visit a friend who was receiving medical care there. It was during Ramadan, and I told the shopkeeper that I had been noticing the chanting on loudspeakers emanating from all the mosques to announce evening prayers were particularly beautiful, almost like music. "It is not music," he corrected me with a serious tone in his voice, "but it is understandable why you find these sounds beautiful, because they are chanting the words of Allah from the Koran."

I am not Moslem, but my parents were fervent Christians and instilled in me a deep respect for religious feelings. I replied to the Syrian gentleman that of course it was a perfectly reasonable explanation. Somehow you had to be there during Ramadan season to appreciate and understand what I meant. On some evenings, those chanting sounds floating through the cool desert air caused me to veer in my strolling in the direction of one mosque or another. In that part of Riyadh, across the street from a large ship-shaped restaurant and hotel, near a major shopping center, there is a tall mosque whose turret at night is bathed in green and gold light, which is absolutely awe-inspiring.

In the cowboy novel I just finished reading, the first-person narrator, Levi, one of the Montana cowboys, is riding together with Rostov, the captain of the troop of Russian cossacks, and asks him, "Do you believe in God?"

That is the conceptual ground where individuals from different places and different traditions can always meet -- if we are willing to acknowledge that one culture is never superior to another, that one set of values inevitably overlaps with all other sets of values.

One late afternoon, I was in a makeshift office at King Saud University's preparatory year program, typing some notes on ideas for improving the curriculum and instruction for students with disabilities. I had heard often of a man named Mazhar, who was in charge of professional development in the intensive English program at KSU-PY, and I had figured we would eventually meet each other. As it happened, the otherwise empty hallways outside the room where I was working were suddenly filled with the sounds of two men walking and speaking to each other in Arabic. They were not looking for me, but when they stopped outside my door, I realized one of them was Mazhar, and I stood up and introduced myself.

The room was dim with the fading sunset through the windows and I had not yet turned on lights, so we shook hands and spoke briefly in near darkness in a nearly deserted building. I had a chance to describe to Mazhar my vision of how a system of universal design could be introduced throughout the institution, and he politely listened, before taking leave and continuing his walk with his companion.

A week later, he asked me and my colleague, Mowbray Bates of Ireland, to develop a modified classroom observation protocol incorporating UDL principles. It was such an exciting day and a half working on that project, and as I turned in our work to Mazhar, it was my hope that we had started an important process of change there.

It wasn't a foreign country when I worked at Lamar Community College in the southeast "desert" of Colorado, but it was similar to some of the cross-cultural experiences I have had, and I learned a lot of valuable lessons there. The college had a very cohesive administration dynamic, and it was easy to stay in touch and keep in the loop on multiple projects and initiatives, through a combination of e-mail, telephone, and no more than 75 steps separating any two buildings. My boss was Del Chase, at that time the vice-president of instruction, who had developed the agriculture program at LCC and lived with his family on a ranch in the area. We were always talking to each other and he oriented me to the IT system and basic policies and procedures during my first few months in the post of director of adult transition services. The learning curve was steep and I spent long hours past closing time each day making sure I would be ready to hit the ground running every morning. On Fridays, however, I would head to the train station for the seven-hour ride home to see my wife and youngest son. One Friday afternoon, I either took the 15 steps over to Del's office or saw him in passing on the sidewalk, and we stopped to talk for a second, at the end of a very hectic work week. "I bet you'll enjoy relaxing for a couple days now," I said to him, and he answered, "You think I'll be relaxing? I have to move 200 head of cattle this weekend."

That was not an unusual situation at Lamar, where many staff members at the college were also full-time farmers and ranchers. The work environment at Lamar was similar to two other places where I have spent time as an educator: Chubu University in Kasugai, Japan, and Fort Hays State University, in Hays, Kansas. On a small college campus, there is a tighter sense of community than at larger places or in more urban settings. Chubu was founded only two or three generations ago by an energetic and visionary engineer, Professor Kohei Miura. I remember that once a year the faculty was invited to ride a bus out to an extensive shrine dedicated to the memory and spirit of the founder. At Fort Hays, as was also true at Chubu and Lamar, it feels natural to take short walks over to a person's office to solidify consensus on developing projects, in concert with phone calls and e-mails. Volga German heritage and farming are essential aspects of the Hays community, but so is the enthusiasm and optimism generated from the university, which responded to state-wide political battles and budget cuts this year by building its own windmill to reduce energy costs by thousands of dollars.

As a native Kansan, my early exposure to the "can-do" spirit while growing up in a "can-do" household with guidance from "can-do" parents and instruction from "can-do" teachers has made it natural for me to recognize and gravitate towards people with that same character when I have lived and worked abroad, or really anywhere I have lived.

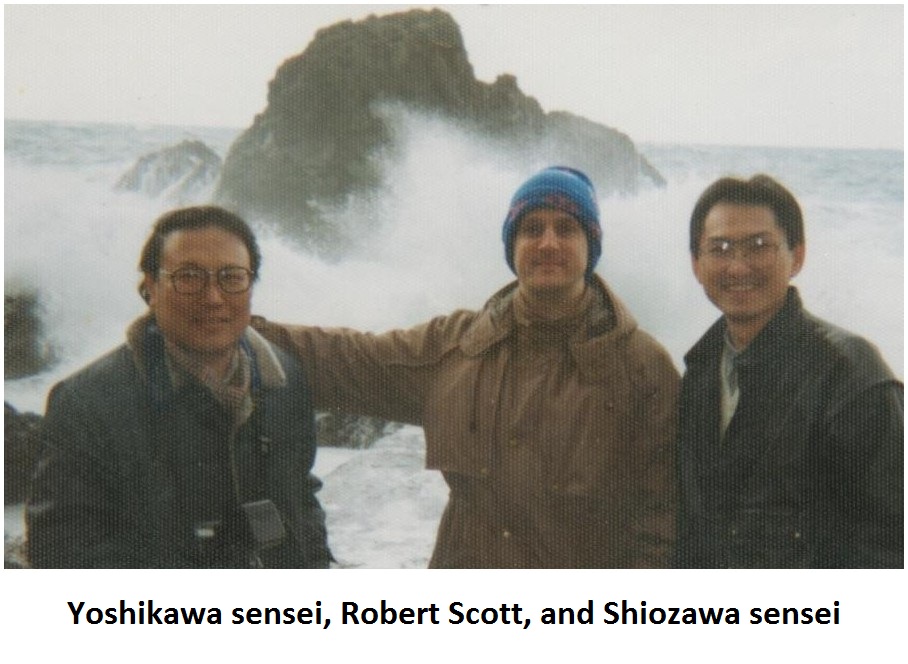

That positive spirit and adventurous character form the common thread that connects so many individuals with whom I have labored and conversed. I think of Tadashi Shiozawa at Chubu University and the joint Language Teaching Study Group that we started to encourage sharing between our Japanese and American colleagues. In New York, there was Jack McLaughlin, and walking down Amsterdam Avenue towards the old Boomer's bar and grill while chewing on cigars. In Nakajo, my friendship with the artist and teacher Daniel Castelaz began, with arguments about sports which eventually developed into our classes competing on fiction-writing activities. In Tokyo, drinking plum wine with Patrick Henry of Jamaica, and the two of us coming up with the idea of bringing flowers for our boss, Jane Bauman, the next day at the last teachers meeting of the school year before she would return home to Reno. And drinking Pilsener at a little bar in Quito with my boss, Gary Dibble, the Vietnam Veteran who suggested to me I ought to read up on American history before getting into any more conversations on that topic [Howard Zinn's "A People's History of the United States" served that purpose as I followed his advice less than a year later]. Monty Thompson, a student and teacher in Lamar, was always up for another "b.s. session with Robb Scott," and more importantly showed me by example exactly how student-centered, project-based instruction works, with his powerfully motivating career development courses for recipients of social assistance in Prowers County.

This is one of those lists that would go on and on if I were not worried about overly trying the patience of any reader who is still searching for the conclusion of this article.

The other day, I was listening again to a song from a couple years ago by Mary Chapin Carpenter--"We've Traveled So Far." I got pretty excited about this song when it was popular on the local radio in Lamar, and it tends to bring up many of the feelings of nostalgia and regret which inevitably accompany memories from international and cross-border sojourns, at least for me.

I sometimes tell the story of my experience with "natto," which is a Japanese delicacy made from fermented soy beans. It is a little bit sticky and gooey, and the first time I ate it, which was the first time I was invited to someone's home for a meal in Nakajo, I picked up some of it from my plate with the chopsticks I was just beginning to get the hang of using, put it in my mouth and [since my mother taught me the importance of having a "cosmopolitan taste and trying anything that is presented at the dinner table"] swallowed the natto. Immediately my internal bodily alarm system went off, and I spent the next half an hour smiling and quietly recovering my composure and getting past the nausea.

I ate everything else presented to me over the next several years in Japan, except that I assiduously avoided trying natto again, based on that initial impression. However, a few days before leaving the country and returning to my homeland, my students invited me out for a farewell dinner, and the table was filled with sushi, sashimi, etc, including the dreaded natto. Nearly five years after my first experience with this food, for some reason I felt inspired to give it another try, and I was so pleasantly surprised to find that it tasted nice and did not provoke an upset stomach.

When the cossacks gave each of the remaining cowboys an amulet filled with Siberian soil, and the cowboys left their favorite Montana horses with their cossack counterparts, it was a fitting ending to Claire Huffaker's story. When we are fortunate enough to momentarily "trade places" with a new friend from a faraway land or a distant perspective, we change in very important and very good ways that influence everything else we experience in life from that point on.

This fall and winter, one of my daughters is traveling to Iceland and later to a friend's wedding in India. Another daughter and my granddaughter live in Ecuador. My older son helps immigrants navigate the legal system in New York City and also is often an international traveler himself. My younger son, still in grade school, is proud of his Colombian heritage and converses comfortably and confidently in both English and Spanish.

Experience in different cultures, languages, and traditions can improve our ability to understand new situations, challenges, and problems. Most important are the relationships we form across differences. As a philosopher friend of mine recently shared with me, there is a quote by George Bernard Shaw:

Article by Dr. Robert Bruce Scott, Ed.D.

drrobbscott@gmail.com

Manhattan, KANSAS

2013 ESL MiniConference Online

PDF conversion by PDF Online